In two days we will celebrate Epiphany (ἐπιφάνεια, “manifestation”, “striking appearance”) the festival concluding the Twelve Days of Christmas. In the Polish tradition it is usually called the Feast of the Three Kings. The Dutch priest and author Johan M. Pameijer, who died last year, wrote in his book ‘De Mythe van Christus. De Zevenvoudige Weg van Kribbe naar Kruis’:

In those days people really believed that the stars would proclaim the birth of the awaited

king of the world. How vivid this expectation was is shown by the following fragment from the Roman poet Virgil who wrote already about the year 40 BC: “O Pure Diana, be kind with regard to the birth of the boy with which the iron era of the world will finally end, and the golden age will come. Your brother Apollo already went to rest. The boy will receive divine life and see heroes accompanied by gods in order to become himself the king of peace in the empire founded by his mighty father. Yet first, o boy, the earth shall pay you homage with small gifts that will not require the work of the peasant: ivy branches, lotus flowers, myrrh and acanthus in festive abundance.”

So as can be seen the coming of the divine king was inscribed in the collective subconscious of humanity. For some day he had to reveal himself, he who shall accomplish the transformation, transform chaos into harmony. The followers of Zarathustra awaited the Saoshyant, the Hindu awaited the Kalki-Avatar, Buddhists the Maitreya-Buddha and Jews the Messiah. Even in our times the hope for the second coming of Christ has not been lost entirely. People would look up onto the sky waiting for a sign – a concentration of divine light. Science let itself be led astray – looking for a historical sign, it thought it found it in the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, which took place a few years before the beginning of our era. More or less at that time the overlapping of the two planets were to create an impression of a star of an extraordinary size and radiance. What goes unacknowledged is the symbolical aspect of the story. The star is a metaphor. As a representation of the divine light, which has to be kindled in the heart of humanity, it announces the birth of the archetypal Redeemer. It is supposed to bring people wisdom, which they need to see that they had found themselves in the claws of foolishness. That is why the legend tells about a star which hits the earth like a lightning strike and becomes a Child. The story is filled with symbolic clues. There are three Wise Men and they bring three gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Of what use is gold, frankincense and myrrh to a newborn child? We can of course ask this question. It seems that those are misguided gifts for poor travelers, for whom, as St. Matthew’s colleague St. Luke testified, there was no room at the inn. Yet in the light of this archetypal story they reveal great perspectives. In all their aspects they point further than to this one child, who is also symbolic. In its quiet humility it represents the whole slumbering humanity that has to be awoken.

These peculiar gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh, are given to every human being at their coming on earth. Gold symbolizes the divine origin from which they proceed and take on material body. Myrrh points at suffering related to life on the earth. Frankincense symbolizes redemption achieved by means of dedicating oneself to the divine. Thus these three gifts entail the earthly birth, life on the earth and return to God. The number of the Wise Men also completely fits in this tradition. In almost all known religions God reveals himself in the form of three principles. Numerous examples from Scripture emphasize the deep meaning of the number three. The way of Jesus’ life leads from the three kings to the three crosses on Calvary.

Source : Johan M. Pameijer, “De Mythe van Christus. De Zevenvoudige Weg van Kribbe naar Kruis”, Deventer 1998, pp. 31-33.

But the visit of the three mysterious Wise Men is not the only content of Epiphany. It is not even the original content. In the Catholic Encyclopedia we read: ‘Owing no doubt to the vagueness of the name Epiphany, very different manifestations of Christ’s glory and Divinity were celebrated in this feast quite early in its history, especially the Baptism, the miracle at Cana, the Nativity, and the visit of the Magi.’ And in Wikipedia we can find the following about the beginnings of the festival and the meanings ascribed to it:

Christians fixed the date of the feast on January 6 quite early in their history. Ancient liturgies noted Illuminatio, Manifestatio, Declaratio (Illumination, Manifestation, Declaration); cf. Matthew 3:13–17; Luke 3:22; and John 2:1–11; where the Baptism and the Marriage at Cana were dwelt upon. Western Christians have traditionally emphasized the “Revelation to the Gentiles” mentioned in Luke, where the term Gentile means all non-Jewish peoples. The Biblical Magi, who represented the non-Jewish peoples of the world, paid homage to the infant Jesus in stark contrast to Herod the Great (King of Judea), who sought to kill him. In this event, Christian writers also inferred a revelation to the Children of Israel. Saint John Chrysostom identified the significance of the meeting between the Magi and Herod’s court: “The star had been hidden from them so that, on finding themselves without their guide, they would have no alternative but to consult the Jews. In this way the birth of Jesus would be made known to all.”

The earliest reference to Epiphany as a Christian feast was in A.D. 361, by Ammianus Marcellinus St. Epiphanius says that January 6 is hemera genethlion toutestin epiphanion (Christ’s “Birthday; that is, His Epiphany”).He also asserts that the Miracle at Cana occurred on the same calendar day.

In 385, the pilgrim Egeria (also known as Silvia) described a celebration in Jerusalem and Bethlehem, which she called “Epiphany” (epiphania) that commemorated the Nativity of Christ. Even at this early date, there was an octave associated with the feast.

In a sermon delivered on 25 December 380, St. Gregory of Nazianzus referred to the day as ta theophania (“the Theophany”, an alternative name for Epiphany), saying expressly that it is a day commemorating he hagia tou Christou gennesis (“the holy nativity of Christ”) and told his listeners that they would soon be celebrating the baptism of Christ. Then, on January 6 and 7, he preached two more sermons, wherein he declared that the celebration of the birth of Christ and the visitation of the Magi had already taken place, and that they would now commemorate his Baptism. At this time, celebration of the two events was beginning to be observed on separate occasions, at least in Cappadocia.

Saint John Cassian says that even in his time (beginning of the 5th century), the Egyptian monasteries celebrated the Nativity and Baptism together on January 6. The Armenian Apostolic Church continues to celebrate January 6 as the only commemoration of the Nativity.

Source

Then why do we refer in this post in the first place, or even exclusively, to the story about the Three Kings/Wise Men/Magi, which is popular in the West (and even here doesn’t constitute the only content of the feast)? In the first place because of its universal dimension. Undoubtedly one of the most controversial Episcopalians of recent years, Bishop John Shelby Spong, writes:

God is not a Christian, God is not a Jew, or a Muslim, or a Hindu, or a Buddhist. All of those are human systems which human beings have created to try to help us walk into the mystery of God. I honor my tradition, I walk through my tradition, but I don’t think my tradition defines God, I think it only points me to God.

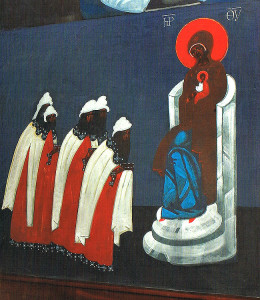

For many such words mean infidelity to Christ as “the way, the truth and the life” (John 14:6). Yet they forget that Christ is not owned by Christians of Christianity. His mystery cannot be identified with any religion or contained in any doctrinal system. We too honor our tradition, but we protest against its idolatrous glorification, which replaces the living reality of Christ with dogmatic pronouncements about him. Christianity produced an amazingly elaborate and deep Christology. We treat it probably with even more respect than Bishop Spong. And yet we also affirm these words of Jerzy Nowosielski:

It’s my dream that Christology enters every religious system. Christ is actually beyond religion… this is the meaning of the adoration of the Three Kings. It seems to me that it’s a prophetic vision of Christ being accepted by the Eastern religions. For I cannot image for example that the Hindu will convert to Christianity. Rather, while remaining Hindu, they will realize the true role of Christ, accept Christ into their religious consciousness. And this is the meaning of the Adoration of the Magi. The Hindu have already partly accepted Christ in their concept of the Bodhisattva. For this whole concept is, in my opinion, a repercussion of the Christological intuitions. But once they accepted him completely into their religious system it will be true ecumenism.

Source : Podgórzec J., “Rozmowy z Jerzym Nowosielskim”, Kraków 2009, p. 144.

Another aspect of the story about the Three Kings, yet directly related to the former one, was pointed to us by The Rev. Dr. Sam Wells, Visiting Professor of Christian Ethics at King’s College, London, former Dean of Duke University Chapel and now Rector at St. Martins-in-the-Fields, London. In his book “What Anglicans Believe. An Introduction” he uses this story as an illustration for the relation between the human ability to know God “naturally” and revelation.

The wise men beheld a star in the heavens: here is the language of natural revelation. They responded and made their way to Jerusalem. Thus it is possible to be drawn towards God without Scripture. The wise men were close to the truth of Christ’s birth — but a miss was as good as a mile. Without Scripture it is not possible to know the heart of God, to meet the incarnate Jesus. When the wise men came to Jerusalem the scribes explored the Scriptures and found that the Messiah was to be born in Bethlehem: here is a moment of special revelation. The wise men then made their way to Bethlehem, to find something natural revelation could never have disclosed: a vulnerable baby, born in humble circumstances yet proclaimed as the Son of God. The story thus portrays the two kinds of revelation harmoniously balanced in bringing people face to face with God. It offers a model for Christian understandings of other forms of knowledge, such as science, and of other forms of faith, such as Islam and Buddhism. The lesson of the story of the wise men is that general revelation may get one to `Jerusalem’; only special revelation may get one that short but crucial extra step to ‘Bethlehem’.

For someone who had to do with classical Christian reflection on this topic there is nothing new in this approach. At least since St. Thomas Aquinas Christians have seen the continuity of the cognitive powers of the human mind and God’s revelation in this way. But it seems like today on the one hand church people declare fidelity to this vision (unless we have to have to do with a follower of the Swiss Reformed theologian Karl Barth, who radically denied any possibility of “natural theology”), and on the other demonstrate fundamental suspicion towards the cognitive activity of the human being with regard to the spiritual/religious sphere, especially when it leads to questioning the doctrine of the church. It seems like the churches are more and more afraid of losing their monopoly as the “channel” of revelation and at the same time the inspector of all human ideas related to that sphere. Though they usually agree – and even like to emphasize – that human reason and experience may point one to God, using Wells’ metaphor – “to Jerusalem,” it seems as if they wanted us to leave our critical thinking and questioning there – also with regard to Scripture and Tradition – and be led further by the “teaching authority of the church.” It is perhaps worthwhile to remind in this context the words of Archbishop Michael Ramsey which we recently quoted on the blog:

… Anglican theology has again and again been ready—while upholding the uniqueness of Christ and the holy scriptures—to see the working of the divine Logos in the world around. For instance, when in the last century the belief in divine revelation found itself confronted by new developments in the secular sphere, like historical criticism, evolutionary biology, and so on, it did not say these things were of the devil. No, it was ready to say that these things are themselves part of the working of the divine Logos in the human mind, reason, and conscience, and it is possible for us to be learning from the contemporary world even where the world seems unpromising, because the divine Logos who is working in the world around us is the same Logos who is incarnate in Christ.

The topic of the relation between human cognitive activity, manifested among other things in scientific research, greatly interested also Br. Paweł – the Rev. Prof. K.M.P. Rudnicki, the priest ministering in the Polish Episcopal Network, a Mariavite theologian and renowned scientist. Lukasz has written an article about the epistemological theory he used in his work. You can read the whole article here and below we reproduced a fragment:

… Rudnicki believes theology relies on experiences of the spiritual world. Theology based solely on a rational elaboration of tradition, which is the sum total of spiritual experiences and commentaries to it, is as dry and unproductive as science would be if it lost the ability or refused to conduct new research and merely added footnotes to what has already been described, examined, demonstrated. So, for example, he claims that Christian dogmas should be the object of spiritual research, and that such research in fact enabled him to understand them better. He challenges the popular opinion that science deals with objective facts and religion is the domain of opinions by stating that the ability to experience the spiritual world is rare, and conflicts of opinion (which are not absent in science also) result rather from different philosophies, rational frameworks, than different experiences. He explains the fact that many scientists are unable to penetrate into the spiritual world by comparing this to a dialogue of someone who suffers from color blindness and a healthy person – it is impossible for the one who sees colors to communicate to the other exactly what they are or even convince him that they in fact exist. The difference with the ability to penetrate spiritual worlds consists in the fact that color blind people are the minority and “spirit blind” people constitute the majority, and in the ability of basically everyone to develop skills necessary to acquire spiritual insight. In the same vein, he points out that not everyone is able to verify complicated scientific theories. Even if one were given the apparatus to conduct experiments regarding quantum mechanism, he wouldn’t be able to do it unless he were properly educated and possessed the intellectual capacity to interpret very complex results and understand the existent theory. People in fact assume that scientific theories are correct, sometimes simply trusting science and sometimes because they have expertise in their own field of research and can understand the methodology of others to a large degree. Similarly, people accept some religious truths, sometimes because they were simply taught to do so, sometimes because they trust the institutions, and sometimes because they have experienced something of them themselves. There is thus harmony between science and religion, because the principle is the same: to gain knowledge and to act in a scrupulous way with goodwill, conducting one’s own research and trusting the results obtained by others.

Thus reflections on the meaning of a feast which is for many at best a – equally fairytale-like as the rest – crowning of the celebration of Christmas have led us into areas we wouldn’t have anticipated: relations between faith and knowledge, human cognition and God’s revelation, different religions and also individual faith experience, and even esoteric experience. There will certainly be enough to ponder on this weekend and next Monday…