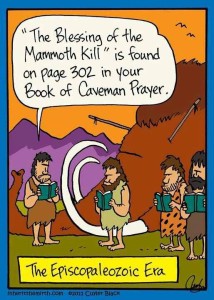

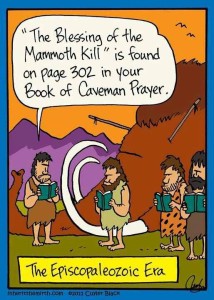

Kilka dni temu umieściłem na Facebooku ten zabawny rysunek, przedstawiający gromadę sympatycznych

jaskiniowców, którzy po upolowaniu mamuta zbierają się na modlitwę dziękczynną. Najwyraźniej są episkopalianami (co stanowi nieodparty dowód na starożytny charakter naszej tradycji ;)), ponieważ jeden z nich mówi: „Ryt błogosławieństwa na okoliczność zabicia mamuta znajdziecie na stronie 302 waszego Jaskinownika Powszechnego”. Nie ma co ukrywać, że mocno zdziwił mnie komentarz, który po jakimś czasie znalazłem pod tym rysunkiem:

jaskiniowców, którzy po upolowaniu mamuta zbierają się na modlitwę dziękczynną. Najwyraźniej są episkopalianami (co stanowi nieodparty dowód na starożytny charakter naszej tradycji ;)), ponieważ jeden z nich mówi: „Ryt błogosławieństwa na okoliczność zabicia mamuta znajdziecie na stronie 302 waszego Jaskinownika Powszechnego”. Nie ma co ukrywać, że mocno zdziwił mnie komentarz, który po jakimś czasie znalazłem pod tym rysunkiem:

widzę dosyć często u Ciebie memy odwołujące się do Episkopalnych wiecznie szukających czegoś w książce (nawet zapamiętałem przez te memy, że jest to “The Book of Common Prayer”). Tylko ja dalej nie wiem o co chodzi czy to ma być obrazowanie Epików jako ludzi mających wytyczne i instrukcje na każdą funkcję życiową i działanie ludzkie? o co cho?

Przede wszystkim ucieszyłem się z określenia „Epicy”. Czyżbyśmy się już dorobili własnej „ksywki” w języku polskim? Jeśli tak, to trudno nie uznać tego za swoisty dowód popularności. Jednak treść komentarza na moment odebrała mi mowę. Czy to możliwe, że ktoś naprawdę podejrzewa nas o bycie ludźmi, „mającymi wytyczne i instrukcje na każdą funkcję życiową i działanie ludzkie?”. Po chwili zastanowienia doszedłem jednak do wniosku, że właściwie nie ma się czemu dziwić. Szczególna relacja, która istnieje pomiędzy anglikanami i ich Modlitewnikiem może wywoływać nieporozumienia, zwłaszcza wśród ludzi, którzy dotąd nie zetknęli się z anglikańską duchowością. Dlatego postanowiłem, zamiast bezpłodnie dziwić się, skreślić na ten temat kilka słów.

Kościół bez właściwości?

W latach 1921-1942 austriacki pisarz awangardowy Robert Musil napisał powieść zatytułowaną „Człowiek bez właściwości”. Jej główny bohater, Ulrich, to człowiek nie posiadający wyraźnego oblicza, jasno sformułowanych cech osobniczych, a może raczej w dziwny sposób wobec nich obojętny. Niekiedy w podobny sposób opisuje się anglikanizm. W pewnym stopniu odpowiada to rzeczywistości. Mówiłem

o tym w kazaniu

wygłoszonym na rekolekcjach w Kiekrzu koło Poznania we wrześniu 2012 r., na których podjęliśmy decyzję o powstaniu Polskiej Wspólnoty Episkopalnej:

Jednym z celów, dla których spotkaliśmy się tutaj, jest poznanie tradycji anglikańskiej. Nie ma w tym zatem nic dziwnego, że jako prowadzący wczoraj i przedwczoraj wciąż na nowo konfrontowani byliśmy z pytaniem o „specyfikę” tej tradycji, o jej charakterystyczne cechy. W co wierzą anglikanie? Jak się zapatrują na taką czy inną kwestię? Jak się modlą? To wszystko składa się na jedno podstawowe pytanie: Czym właściwie jest anglikanizm? Krok za krokiem stawało się coraz jaśniejsze, że cechą szczególną anglikanizmu jest to, że… właściwie nigdy nie chciał mieć on żadnych szczególnych cech, że chciał być po prostu chrześcijaństwem – w jakimś sensie bezprzymiotnikowym, pozbawionym zbędnych dookreśleń. Gdy zaś jakieś przymiotniki się pojawiły, to takie, które wskazują na niemożliwość umieszczenia nas w jakiejś gotowej szufladzie, którą znamy z historii Kościoła. Mówiliśmy na przykład o tym, że Kościoły anglikańskie są (zarazem) katolickie i reformowane. Katolickie, bo podkreślają ciągłość chrześcijańskiej tradycji od jej zarania, i reformowane, bo są świadome potrzeby krytycznego obchodzenia się z nią, czego wyrazem była nie tylko reformacja XVI w., ale także wiele innych, późniejszych reform i przemian. Jeśli spełniliśmy swoje zadanie właściwie, w toku tych rozmów powinno było okazać się jeszcze coś innego – że zdaniem anglikanów na pytanie o to, czym jest chrześcijaństwo, często nie da się odpowiedzieć inaczej aniżeli następnym pytaniem, które potem zrodzi kolejne pytanie, itd., itd…

Poszukiwacze „twardych tożsamości”, oczekujący od Kościoła odpowiedzi na wszystkie możliwe pytania, bez wątpienia rozczarują się w kontakcie z anglikańskim sposobem bycia chrześcijaninem. Na tle innych wspólnot reformacyjnych anglikanizm wyróżnia się brakiem własnej konfesji, porównywalnej z Augsburskim Wyznaniem Wiary czy Konfesją Helwecką, oraz katechizmu takiego jak Mały i Duży Katechizm Marcina Lutra czy Katechizm Heidelberski. Dlatego jest nam często trudno jednoznacznie odpowiedzieć na pytanie o cechy szczególne naszego Kościoła. Jednak problem nie polega na tym, że ich nie ma! Wbrew pozorom, Kościoły anglikańskie jednak nie są „Kościołami bez właściwości”. Rzecz w tym, że nie znajdzie się ich w żadnym dokumencie doktrynalnym. Ich nośnikiem i wyrazicielem jest liturgia – sposób w jaki wspólnie modlimy się, „oddając cześć Bogu w pięknie świętości”. Anglikanizm można traktować jako ucieleśnienie starokościelnej zasady „lex orandi, lex credendi” (w parafrazie: „jak się modlisz, tak wierzysz”). Pod tym względem wykazuje on wiele cech wspólnych z prawosławiem. Równie często, jak słyszy się słowa „prawosławie to liturgia”, przytacza się sformułowanie Arcybiskupa Canterbury Michaela Ramseya (1904-1988), który stwierdził, że teologia anglikańska uprawiana jest „w rytm kościelnych dzwonów”. Dlatego właśnie naszą „księgą wyznaniową” nie jest konfesja ani katechizm, lecz modlitewnik.

„So far so good”, jak mawiają Anglicy, jednak w praktyce okazuje się, że anglikańskie przywiązanie do Modlitewnika budzi nieporozumienia.

Czy to naprawdę „modlitewnik”?

Może należałoby zacząć od samej nazwy. Z czym kojarzy nam się słowo „modlitewnik”?

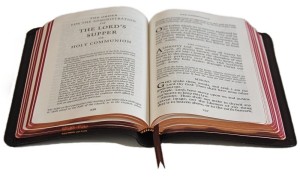

Mam nieodparte wrażenie, że większość Polaków na jego dzwięk widzi przed sobą „książeczkę do nabożeństwa”, z której wystają mniej lub bardziej kiczowate „święte obrazki” i która spoczywa na półce tuż obok moherowego beretu babci. Od razu chciałbym zaznaczyć, że, pomimo obecnej w tych słowach ironii, naprawdę nie zamierzam nimi nikogo urazić. Chodzi mi jedynie o to, by jasno powiedzieć, że książka, którą nazywamy Modlitewnikiem Powszechnym, jest – mimo zbieżności nazw – czymś innym. Już na pierwszy rzut oka widać, że łączy ona ze sobą cechy brewiarza i mszału, ale zawiera też szereg elementów, które wykraczają poza te określenia. Niekiedy wydaje mi się, że słuszniej byłoby o nim mówić jako o „niezbędniku anglikanina”, zawierającym minimum rzeczy, które należy zabrać ze sobą, wyruszając w „anglikańską drogę”. Pomimo jednak, że termin „modlitewnik” nie do końca pokrywa się z jej zawartością, fakt, że to minimum zostało ujęte w formę zbioru modlitw liturgicznych, a nie np. traktatu teologicznego, ma ogromne znaczenie. Wskazuje on bowiem na to, że, aczkolwiek doskonale zdajemy sobie sprawę z tego, iż pomiędzy liturgią i doktryną ma miejsce sprzężenie zwrotne (to znaczy, że wpływają one na siebie nawzajem), z naszego punktu widzenia znaczenie podstawowe ma to, że modlitwa kształtuje doktrynę.

Mam nieodparte wrażenie, że większość Polaków na jego dzwięk widzi przed sobą „książeczkę do nabożeństwa”, z której wystają mniej lub bardziej kiczowate „święte obrazki” i która spoczywa na półce tuż obok moherowego beretu babci. Od razu chciałbym zaznaczyć, że, pomimo obecnej w tych słowach ironii, naprawdę nie zamierzam nimi nikogo urazić. Chodzi mi jedynie o to, by jasno powiedzieć, że książka, którą nazywamy Modlitewnikiem Powszechnym, jest – mimo zbieżności nazw – czymś innym. Już na pierwszy rzut oka widać, że łączy ona ze sobą cechy brewiarza i mszału, ale zawiera też szereg elementów, które wykraczają poza te określenia. Niekiedy wydaje mi się, że słuszniej byłoby o nim mówić jako o „niezbędniku anglikanina”, zawierającym minimum rzeczy, które należy zabrać ze sobą, wyruszając w „anglikańską drogę”. Pomimo jednak, że termin „modlitewnik” nie do końca pokrywa się z jej zawartością, fakt, że to minimum zostało ujęte w formę zbioru modlitw liturgicznych, a nie np. traktatu teologicznego, ma ogromne znaczenie. Wskazuje on bowiem na to, że, aczkolwiek doskonale zdajemy sobie sprawę z tego, iż pomiędzy liturgią i doktryną ma miejsce sprzężenie zwrotne (to znaczy, że wpływają one na siebie nawzajem), z naszego punktu widzenia znaczenie podstawowe ma to, że modlitwa kształtuje doktrynę.

Nieporozumienia i problemy

Nie mniejsze zdziwienie aniżeli komentarz na Fecebooku, który dostarczył mi inspiracji do napisania tego tekstu, wywołała u mnie to, że ktoś niedawno zinterpretował ten fakt jako wyraz niedoceniania roli teologii w Kościele. Teologia jest dla tej osoby bardzo ważna i dlatego właśnie wyraziła ona swój dystans do słów, które zawarliśmy w

naszym folderze informacyjnym

:

Anglikanizm opiera swoją specyfikę raczej na liturgii aniżeli na rozważaniach teologicznych. Dlatego jedyna naprawdę adekwatna odpowiedź na pytanie, czym on jest, brzmi: przyjdź na nasze nabożeństwo, aby oddać Bogu cześć i chwałę “w pięknie świętości” (Ps. 28[29]). Zapraszamy!

Moje zdziwienie wynikało przede wszystkim z faktu, że sam również uważam się za człowieka, dla którego teologia jest bardzo ważna. Do tej pory w życiu spotykałem się raczej z zarzutem, że jestem „za bardzo teologiem”, aniżeli z podejrzeniem, iż chciałbym deprecjonować znaczenie refleksji teologicznej. Tradycja anglikańska, nawet jeżeli nie zrodziła zbyt wielu teologów tej miary, co teologiczni luminarze kontynentalnego protestantyzmu (bądźmy jednak szczerzy, również w Kościołach ewangelickich Lutrowie, Bohoefferowie czy Barthowie nie rodzą się na kamieniu!), także nie podważa znaczenia dobrej teologii dla Kościoła. W końcu nie bez powodu na konferencji Polskiej Wspólnoty Episkopalnej, która odbyła się w styczniu tego roku, poświęciliśmy tyle uwagi formacji naszych liderów, w tym również formacji teologicznej. Aczkolwiek trudno sprowadzać wszystko do poziomu wykształcenia, nie ma chyba wątpliwości, że nawet w niełatwych warunkach polskich, które nakładają na nas określone ograniczenia, PWE w żadnym razie nie chce być wspólnotą, w której “nie matura, lecz chęć szczera…”. Pomimo wszystkich trudności, czujemy się zobowiązani realizować to,

o czym swego czasu pisał

zwierzchnik Konwokacji Kościołów Episkopalnych w Europie, bp Pierre Whalon:

Inny aspekt anglikańskiej metody stanowi akcent na oświatę i naukę. Oczywiście, dzielimy to z innymi chrześcijanami: Kościół, który nie naucza, w ogóle nie jest Kościołem. Nasze szczególne podejście do tradycji wymaga jednak wspólnotowego namysłu, który naszym zdaniem musi opierać się na jak najszerszym dostępie do informacji.

Dla anglikanów było zawsze ważne, aby ten akcent na oświatę i naukę nie oznaczał jedynie kładzenia nacisku na teologię. To właśnie dlatego refleksja anglikańska sprawia często wrażenie mocno zakorzenionej w ogólnej refleksji humanistycznej, w literaturze, sztuce, poezji czy w naukach ścisłych. Jednak na pewno nie oznacza to niedoceniania roli teologii jako takiej. Co więc chcieliśmy wyrazić zdaniem, które wywołało wątpliwości czy nawet opór? Przede wszystkim to, że nie ma jednej anglikańskiej teologii. Istnieje ich bardzo wiele i od samego zarania były one uprawiane w możliwie szerokim kontekście ekumenicznym – w dialogu z przedstawicielami innych tradycji. I właśnie ta wielość sprawia, że żadna z nich nie może pełnić roli wyróżnika anglikanizmu. Jednakże wszystkich ich twórców, zwolenników i przeciwników łączyło i łączy jedno – wspólna tradycja liturgiczna.

W ubiegłym roku minęło osiem lat, od kiedy pełnię służbę pastorską w ekumenicznej wspólnocie bazowej

Kritische Gemeente IJmond

w Holandii. Historia ruchu bazowego jest nierozdzielnie związana z przemianami w liturgii. Można powiedzieć, upraszczając nieco sprawę, że jego pierwsi przedstawiciele byli szczególnie gorliwymi zwolennikami posoborowej reformy liturgicznej w Kościele rzymskokatolickim. W każdym razie swoboda podejścia do tradycyjnych form liturgicznych, w tym również możliwość ich daleko idącej rewizji a nawet całkowitego odrzucenia i zastąpienia przez nowe, stała się jednym z haseł wiodących ruchu bazowego. Możliwość odchodzenia od tradycyjnych form liturgicznych, nawet jeżeli w ich miejsce pojawia się po prostu pustka albo intuicyjne przywiązanie do form, które sama KGIJ wytworzyła na przestrzeni czterdziestu kilku lat samodzielnego istnienia, jest dla większości jej członków probierzem wolności w ogóle. Już ze sposobu, w jaki o tym pisze, możecie bez wątpienia wywnioskować, że takie podejście wywołuje u mnie wątpliwości. I rzeczywiście: spotkanie z ruchem bazowym stało się dla mnie tym impulsem, który pchnął mnie w kierunku tradycji anglikańskiej, charakteryzującej się innym podejściem do liturgii. “Innym”, to znaczy jakim, właściwie?

Ludzie, którzy postrzegają Kościół Episkopalny przede wszystkim jako wspólnotę liberalną, zapewniającą swoim członkom ogromną przestrzeń dla własnych poszukiwań duchowych, dziwią się pewnemu “rygoryzmowi liturgicznemu”, który napotykają w PWE. Nie można wykluczyć, że wychodzi tu na jaw jakiś rodzaj “neofickiej gorliwości”. Skoro już wybraliśmy anglikanizm, staramy się go uprawiać “jak należy” i być może nie zawsze w pełni wykorzystujemy wszystkie możliwości kreatywnego obchodzenia się z liturgią. Jest to w każdym razie coś, nad czym, jak sądzę, powinniśmy się zastanowić. Chociaż z drugiej strony nie ukrywam, że moim zdaniem najpierw powinno się wyrobić w sobie pewne nawyki, a potem dopiero – już świadomie – ewentualnie od nich odstępować. Tak czy inaczej nie ulega jednak wątpliwości, że anglikanizm rozumiany w taki sposób, jak rozumie go i praktykuje Polska Wspólnota Episkopalna, nie zadowala nie tylko poszukiwaczy “jasnych odpowiedzi i niepodważalnych prawd”. Również ludziom, którzy liturgiczną “grę” traktują przede wszystkim jako zestaw krępujących reguł i nagromadzenie nudnych, bezdusznych formuł, nie jest łatwo się wśród nas odnaleźć, chyba że są gotowi zrewidować to spojrzenie.

To powiedziawszy, chciałbym jednak jednocześnie podkreślić, że zależy nam na tym, aby

liturgia pozostała, zgodnie z pierwotnym znaczeniem słowa, dziełem człowieka, którego nie otacza żadne tabu. Jeżeli o mnie chodzi, potraktujcie te słowa jako zachętę do zwrócenia mnie samemu i innym liturgom we Wspólnocie uwagi w momencie, kiedy odnieślibyście wrażenie, iż o tym zapominamy. Nie zmienia to jednak faktu, że episkopalianie na pewno nie staną się zwolennikami zastąpienia tradycyjnych form liturgicznych przez improwizowaną modlitwę i wynika to nie z rygoryzmu, lecz z tego wszystkiego, co napisałem powyżej o znaczeniu liturgii jako nośnika i zwornika tradycji anglikańskiej. Luteraninowi czy ewangelikowi reformowanemu, nawet jeżeli czuje się on do pewnego stopnia związany agendami liturgicznymi swego Kościoła, jest łatwiej odstępować od nich, ponieważ zawsze może powiedzieć, że w tym, co robi, w żaden sposób nie narusza treści ksiąg wyznaniowych. Również rzymskokatolik może sobie pozwolić (inna rzecz, czy powinien) na sporą dozę liturgicznej “radosnej twórczości” tak długo, jak długo nie przeciwstawia się dogmatom swojego Kościoła. Anglikanie nie mają jednak ani pism konfesyjnych ani żadnych WŁASNYCH dogmatów (jedynie z przekonaniem składają swój podpis pod nauczaniem Kościoła pierwszych wieków). Mają jedynie swój “niezbędnik”. Kluczem do zrozumienia znaczenia Modlitewnika Powszechnego w tradycji anglikańskiej jest chyba właśnie to, że ów Modlitewnik jest o wiele więcej aniżeli tylko modlitewnikiem. Być może warto, abyśmy się nad tym wspólnie zastanowili w gronie osób tłumaczących The Book of Common Prayer na język polski. Czy nie należałoby szukać innego słowa na wyrażenie zawartości i znaczenia tej księgi?

liturgia pozostała, zgodnie z pierwotnym znaczeniem słowa, dziełem człowieka, którego nie otacza żadne tabu. Jeżeli o mnie chodzi, potraktujcie te słowa jako zachętę do zwrócenia mnie samemu i innym liturgom we Wspólnocie uwagi w momencie, kiedy odnieślibyście wrażenie, iż o tym zapominamy. Nie zmienia to jednak faktu, że episkopalianie na pewno nie staną się zwolennikami zastąpienia tradycyjnych form liturgicznych przez improwizowaną modlitwę i wynika to nie z rygoryzmu, lecz z tego wszystkiego, co napisałem powyżej o znaczeniu liturgii jako nośnika i zwornika tradycji anglikańskiej. Luteraninowi czy ewangelikowi reformowanemu, nawet jeżeli czuje się on do pewnego stopnia związany agendami liturgicznymi swego Kościoła, jest łatwiej odstępować od nich, ponieważ zawsze może powiedzieć, że w tym, co robi, w żaden sposób nie narusza treści ksiąg wyznaniowych. Również rzymskokatolik może sobie pozwolić (inna rzecz, czy powinien) na sporą dozę liturgicznej “radosnej twórczości” tak długo, jak długo nie przeciwstawia się dogmatom swojego Kościoła. Anglikanie nie mają jednak ani pism konfesyjnych ani żadnych WŁASNYCH dogmatów (jedynie z przekonaniem składają swój podpis pod nauczaniem Kościoła pierwszych wieków). Mają jedynie swój “niezbędnik”. Kluczem do zrozumienia znaczenia Modlitewnika Powszechnego w tradycji anglikańskiej jest chyba właśnie to, że ów Modlitewnik jest o wiele więcej aniżeli tylko modlitewnikiem. Być może warto, abyśmy się nad tym wspólnie zastanowili w gronie osób tłumaczących The Book of Common Prayer na język polski. Czy nie należałoby szukać innego słowa na wyrażenie zawartości i znaczenia tej księgi?

Skoro zaś zajęliśmy się już tytułem, warto również zwrócić uwagę na inny jego element. The Book of Common Prayer to dosłownie “Księga Modlitw Powszechnych [albo Wspólnych]”. To, co stara się ona normować, dotyczy więc oficjalnego życia liturgicznego WSPÓLNOTY. Oczywiście Modlitewnika można także używać indywidualnie i jest to dobry anglikański zwyczaj. Nie bez powodu biskup Pierre Whalon scharakteryzował swego czasu anglikanina jako osobę, która modli się z BCP. Z drugiej strony należy zawsze pamiętać, że Kościół Episkopalny nie dyktuje nikomu tego, w jaki sposób ma wyglądać jego indywidualne życie modlitewne. Próbuje jedynie ujednolicić formy modlitwy wspólnotowej. W odniesieniu do tego, jaką modlitwą na przykład każdy z nas rozpoczyna czy kończy dzień, panuje całkowita swoboda i żadna instancja kościelna nigdy nie będzie starała się tej swobody ograniczać.

Skoro padło już słowo “swoboda”, chciałbym poświęcić chwilę uwagi jeszcze jednemu jej aspektowi. Czytając Modlitewnik Powszechny, a zwłaszcza używając go zgodnie z przeznaczeniem, bez trudu zauważymy, że zawarte w nim tzw. “rubryki”, które pełnią rolę podobną do didaskaliów w sztuce teatralnej, informując o tym, w jaki sposób mamy prowadzić liturgię, bardzo często noszą charakter propozycji a nie przepisów. Również niemała cześć zawartych w nim modlitw ma charakter fakultatywny. Tak więc także liturg, który trzyma się rubryk, wciąż dysponuje bardzo dużą przestrzenią, w ramach której może dokonywać własnych wyborów liturgicznych. W polskich warunkach wciąż jeszcze jest to niewystarczająco widoczne, ponieważ tłumaczenie dopiero trwa i wiele opcji liturgiczno-modlitewnych nie jest jeszcze dostępnych w naszym języku. Mamy nadzieję, że gdy wreszcie powstanie polska wersja BCP, stanie się również jaśniejsze, na jak wiele sposobów można kształtować życie liturgiczne polskiego episkopalianizmu, nie wykraczając przy tym poza – naprawdę bardzo szerokie – granice wytyczane przez Modlitewnik.

A czy przyjdzie kiedyś moment na stworzenie polskiego Modlitewnika, który nie byłby tłumaczeniem? Na styczniowej konferencji biskup Pierre zakreślił szeroką perspektywę rozwoju Polskiej Wspólnoty Episkopalnej. Jej działania miałyby prowadzić ku stworzeniu autokefalicznego Kościoła Episkopalnego w Polsce. Taki Kościół mógłby oczywiście podjąć trud stworzenia własnej księgi modlitw.

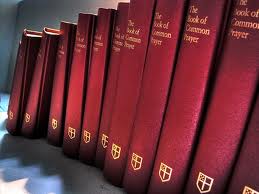

Nie ma jednego Modlitewnika

Ten ostatni wątek naprowadza mnie na trop czegoś, od czego być może powinienem był zacząć. Chodzi o to, że mówienie o jednym Modlitewniku jest właściwie równie mylne, jak, wciąż pokutujące niestety, mówienie o jednym Kościele anglikańskim. Podobnie jak nie istnieje jeden Kościół, lecz wspólnota 38 lokalnych Kościołów anglikańskich, tak istnieje cała szeroko rozgałęziona rodzina Modlitewników. Wszystkie one mają wspólnego przodka w Modlitewniku Powszechnym

Arcybiskupa Thomasa Cranmera

z 1549 r. Następnie Modlitewnik przechodził wiele zmian, które doprowadziły w końcu do powstania wersji z 1662 r., po dziś dzień obowiązującej oficjalnie w Kościele Anglii. Z

czasem pojawiły się lokalne odmiany BCP, które dały początek kolejnym gałęziom modlitewnikowej rodziny. Amerykański Modlitewnik Powszechny z 1979 r., którego używamy w tłumaczeniu na język polski w Polskiej Wspólnocie Episkopalnej, wywodzi się od pierwszego Modlitewnika używanego w Kościele Episkopalnym, który powstał w 1790 r. Opierał się on na angielskim wydaniu z 1662 r. oraz na szkockiej liturgii z 1764 r. Z biegiem czasu miało miejsce kilka kolejnych rewizji tekstu, które doprowadziły w końcu do powstania wersji z 1979 r. Dodać należy, że w anglikanizmie panuje zasada, iż raz zatwierdzony tekst liturgiczny może być odtąd używany zawsze, nawet wtedy, gdy pojawi się nowa liturgia. Anglikanie nie potrzebują więc specjalnych indultów na odprawianie nabożeństw przy użyciu dawnych formularzy liturgicznych, jak dzieje się to w Kościele rzymskokatolickim. I tak np. w parafii Kościoła Anglii w pobliskiej Hadze w każdą pierwszą niedzielę miesiąca odprawiana jest liturgia wg Modlitewnika z 1662 r., na której staramy się bywać kiedy to tylko możliwe. Ciekawą cechę tej liturgii stanowi obecny w niej “polski akcent”. Na kształt Modlitewnika wpłynął bowiem również polski reformator religijny,

Jan Łaski

(1499-1560). To jemu anglikańska liturgia zawdzięcza obecność dziesięciorga przykazań, które, zamiennie z podwójnym przykazaniem miłości, stanowią podsumowanie Zakonu, służące “badaniu sumień”, które ma prowadzić do uznania własnej grzeszności przed Bogiem i potrzeby łaski i miłosierdzia.

czasem pojawiły się lokalne odmiany BCP, które dały początek kolejnym gałęziom modlitewnikowej rodziny. Amerykański Modlitewnik Powszechny z 1979 r., którego używamy w tłumaczeniu na język polski w Polskiej Wspólnocie Episkopalnej, wywodzi się od pierwszego Modlitewnika używanego w Kościele Episkopalnym, który powstał w 1790 r. Opierał się on na angielskim wydaniu z 1662 r. oraz na szkockiej liturgii z 1764 r. Z biegiem czasu miało miejsce kilka kolejnych rewizji tekstu, które doprowadziły w końcu do powstania wersji z 1979 r. Dodać należy, że w anglikanizmie panuje zasada, iż raz zatwierdzony tekst liturgiczny może być odtąd używany zawsze, nawet wtedy, gdy pojawi się nowa liturgia. Anglikanie nie potrzebują więc specjalnych indultów na odprawianie nabożeństw przy użyciu dawnych formularzy liturgicznych, jak dzieje się to w Kościele rzymskokatolickim. I tak np. w parafii Kościoła Anglii w pobliskiej Hadze w każdą pierwszą niedzielę miesiąca odprawiana jest liturgia wg Modlitewnika z 1662 r., na której staramy się bywać kiedy to tylko możliwe. Ciekawą cechę tej liturgii stanowi obecny w niej “polski akcent”. Na kształt Modlitewnika wpłynął bowiem również polski reformator religijny,

Jan Łaski

(1499-1560). To jemu anglikańska liturgia zawdzięcza obecność dziesięciorga przykazań, które, zamiennie z podwójnym przykazaniem miłości, stanowią podsumowanie Zakonu, służące “badaniu sumień”, które ma prowadzić do uznania własnej grzeszności przed Bogiem i potrzeby łaski i miłosierdzia.

—

Pierwotnie planowane kilka słów okazało się ostatecznie jednym z dłuższych postów na naszym blogu. Tak to bywa, kiedy człowiek od dłuższego czasu nosi się z zamiarem czegoś. Dziękując wszystkim, którzy mnie do tego zainspirowali, mam jednocześnie nadzieję, że z kolei moje słowa stanowić będą inspirację do refleksji i dyskusji.

tego świata nie pozwalają, by tak łatwo odbierano im niewolników (pomyślmy choćby o Putinie!). Biedni kaznodzieje wędrowni, jak Jezus, zazwyczaj nie zmieniają biegu historii. Trafiają raczej na jej śmietnik i popadają w zapomnienie. Taki jest ten świat, zaś każdy, kto postrzega go w inny sposób, nie wyrósł jeszcze, jak widać, z krótkich spodenek. I nie myślmy, że coś sobie ułatwimy, zmieniając nazbyt dosłowne podejście do opowieści paschalnych na bardziej metaforyczne czy „uduchowione”. Myśl, że Jezus żyje w oraz przez swoich uczniów i naśladowców, jest właściwie równie problematyczna jak wizja otwartego, pustego grobu. Jedynie wydaje się nieco mniej szokująca, nieco łatwiejsza do pojęcia…

tego świata nie pozwalają, by tak łatwo odbierano im niewolników (pomyślmy choćby o Putinie!). Biedni kaznodzieje wędrowni, jak Jezus, zazwyczaj nie zmieniają biegu historii. Trafiają raczej na jej śmietnik i popadają w zapomnienie. Taki jest ten świat, zaś każdy, kto postrzega go w inny sposób, nie wyrósł jeszcze, jak widać, z krótkich spodenek. I nie myślmy, że coś sobie ułatwimy, zmieniając nazbyt dosłowne podejście do opowieści paschalnych na bardziej metaforyczne czy „uduchowione”. Myśl, że Jezus żyje w oraz przez swoich uczniów i naśladowców, jest właściwie równie problematyczna jak wizja otwartego, pustego grobu. Jedynie wydaje się nieco mniej szokująca, nieco łatwiejsza do pojęcia…