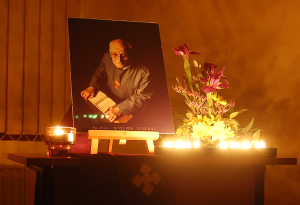

To answer in advance what some of you may ask: no, we don’t intend to return to writing the blog yet. Moreover, we feel a little awkward ourselves, visiting it for the first time since a few months, but we think we need to make up for an important omission. A year ago Br. Pawel, the Rev. Prof. K.M.P. Rudnicki, passed away. The sermon preached at the commemoration service of the Polish Episcopal Network by Jarek was published in print but not on the blog. Today, on the first anniversary of his death, we publish it here as well.

Book of Amos 5:8, Apocalypse 21:2-7, St. John’s Gospel 10:11-16

God didn’t have it easy with me the last couple of days. Time and again, I would ask him if he really thinks that he needs Pawel more than we do. You may consider it strange, for people often say that dealing with the death of our loved ones is easier for us Christians. Yes, in some sense it is easier, but on the other hand the awareness that we offer what happened to God, regardless of how it strikes us, doesn’t alleviate the pain, the loss, the sense of being left alone, even orphaned. It’s one of the paradoxes related to the passing of a man who was a great paradox himself. Paradox will be one of the key words in this reflection. When we asked the Rev. Greg Neal, who only a month ago stood with Br. Pawel at the altar of St. Martin’s [1] , to help us prepare the liturgy for tonight as we thought we didn’t have enough time to do it ourselves before departing from the Netherlands, he chose also the lessons, and explained why. With regard to the Old Testament Lesson from Prophet Amos, he referred of course to one of Pawel’s two main callings, Astronomy. To Amos’ statement, “He who made the Pleiades and Orion,” one would like to add: “he who made Rudnicki’s comet and the supernovae Pawel discovered.” He, whose creating power goes beyond what we can see. It was to studying his creation that Pawel devoted a great part of his life. Every time we were preparing for a service like today, we went through a ritual of sorts: first, we prepared the liturgy, the lessons, and then sent them to Cracow by email, always on the Monday preceding the Saturday on which the service were to be held, because Pawel said, “do it then as on Monday I’m a Theologian, and from Tuesday to Thursday an Astronomer, so otherwise I wouldn’t have enough time to prepare.”I browsed many internet comments below various articles devoted to Pawel, and it was stated repeatedly that he was drawn to God by Astronomy. Some found it odd, some logical. Yet it wasn’t entirely like that, for the events that initiated the spiritual transformation of Pawel – born to a Communist/Socialist family, son of Lucjan Rudnicki, a famous Communist author and of a Polish Socialist Party activist – were more existential than strictly intellectual. I have here in mind in the first place the spiritual experiences he had when he fought in the guerilla armies, first in the People’s Guard [2] and then in the People’s Army. For Pawel was one of those who were “on the wrong side” according to today’s historiography, those who should not be spoken of as they allegedly didn’t “fight for Poland.” I remember some discussions we had, difficult conversations when for example he didn’t let it be spoken ill of such a controversial person like Mieczyslaw Moczar [3] , because he was his commander. Pawel, a Righteous Among The Nations, an honorary citizen of Israel, felt a bond with someone like Moczar, one of those behind the 1968 events [4] . As I said, paradox will be the key word in this reflection. It was this series of spiritual experiences, about which Pawel spoke relatively little – he described them in his spiritual biography – that opened him up to another dimension of reality, the one that cannot be studied by a telescope or a magnifying glass, or a microscope. Into this realm too he journeyed in his characteristic way – he combined such an amazing number of spiritual traditions that no orthodoxy and no heresy would combine them like this one man. I will name only a few.

Anthroposophy [5]

Pawel was one of the greatest Anthroposophists Poland had – it is a spiritual school drawing from the third pillar of European culture, beside the classical and the Christian ones, the pillar of Western esotericism, the Rosicrucian tradition, the tradition of Boehme, etc., etc. It is also an attempt to study, to gain concrete spiritual knowledge of those worlds which our senses cannot penetrate – an attempt to open the inner eye. For this need was in him too. He wanted to be a scholar also with regard to the spiritual world.

Looking for a church for himself

Pawel told many times that he went to the Orthodox Church first – in times that were difficult for it, when it was only reestablishing itself after World War II in an extremely complicated situation. At last he found himself in the Mariavite Church, however. He told that he was fascinated by two things. First, the way the priest looked like: wearing simple, as for those times, vestments, and second, the simple, spiritual piety that he demonstrated in his sermon and in conversation.

One can hardly not associate this with Pawel himself, the way he was with us. In today’s Gospel we heard about Christ – the Good Shepherd. It is also a calling for us all – to be shepherds for others – and especially for those whose vocation is to be leaders in the Church. The way Pawel did it, was the way of the Good Shepherd indeed. What I have in mind is the way he celebrated the liturgy – simple, free from redundant decorative elements, and at the same time revealing a profound experience, a deep awareness of the meaning of each word. Each word of the liturgy, when spoken by Pawel, was full of meaning, was something to be savored, something one had to stop and think about, something that cannot be spoken lightly, because it opens up new spiritual worlds to us. And how did we remember him from the retreats of the Polish Episcopal Network? Whenever we were working on the program, he would send us an email and ask gently, “Will there be time for me to speak about this or that?” It was always only an offer. I remember especially well his last talk at the retreat in Pulawy, where he spoke of his problem with forgiving, and how, step by step, he had been overcoming it and how he had been gradually succeeding in discovering some gift, some opportunity to learn in every difficult person he had to forgive.

Does it mean that we should see the difficult fact of Pawel’s absence among us as an opportunity to learn something? In a sense the time of the exam is coming. The teacher is gone and we will have to show how much we learned as his disciples. Yet we will take this exam aware that He who is the Lord of life and death says, “To him who is thirsty I will give to drink without cost from the spring of the water of life.” Without cost, for free. Pawel was a man who devoted a great part of his writing, his theological and spiritual work to the issue of “work on oneself.” Sometimes we laughed that Work on Oneself is his fourth name, “Konrad Maria Paweł ‘Work on Oneself’ Rudnicki.” Sometimes when you listened to what he said about the necessity of spiritual growth, you would ask yourself if there was a place for the “without cost” – for a gift, for receiving, opening oneself up to grace. Yet who listened to Pawel carefully, certainly understood that work on oneself was not an instrument to gain entrance to heaven, but was meant to make us able to open up to this gift, this living water, to stand before God in a truly conscious manner – as the receiving one, but also as the one who is supposed to do something with the gift she received, let it grow. It is another paradox located in the very heart of Christian spirituality, which is certainly a spirituality of grace, gift, this “without cost” – in a moment we will approach the table and receive the bread that is nothing else but a gift – and yet we will receive it in order to go into the world and be witnesses of our allegiance to the Gospel. So it is at the same time a spirituality of work, an active spirituality.

“And I have other sheep.” One and a half year ago we held the conference initiating the Polish Episcopal Network. About 25 persons said they would come. It was raining on that Saturday. When we arrived together with our guests – Bishop Pierre Whalon and his wife, Melinda, Prof. Daniel Siemiatkoski who came from Oxford – we saw only five people. When I was opening the conference, I didn’t know where to look, how could I look in the eyes of the bishop whom I requested to come from Paris to meet five persons. Yet Pawel was among them, Pawel who thought that since the Episcopal Church granted him, a Polish Mariavite, the permission to minister as a priest in the 60s and 80s, since it offered him an opportunity to do what he considered a need of his soul – being a priest – he should accompany the Polish Episcopal Network when it was taking its first steps in Poland. He saw this as a kind of debt. One and a half year later it is we that owe him. He was with us indeed every time, on every opportunity. He didn’t celebrate a service only once – in January, when he really couldn’t walk. I came then to Sw. Filipa street [6] with reserved sacrament that he had consecrated specially for this occasion at a Mass he celebrated in his study.

“And I have other sheep.” Pawel was a Mariavite. The Work of Great Mercy, Mariavite Spirituality, really became a part of him. He was certainly a troublesome Mariavite for many other Mariavites, and especially Mariavite Bishops, yet a Mariavite in his heart and in his soul nonetheless. And still, during this one and a half year I never doubted that he was also a priest in the Episcopal Church. The license he received in the 60s, which he showed then to Bishop Pierre, was not merely a piece of paper. It was a testimony of his deep bond with us, with the Polish Episcopal Network, with the Episcopal Church, with Anglicanism – with those other sheep, who came God knows whence, sometimes four, sometimes five, sometimes twenty (he would be surprised to see so many today). A month ago someone told me after the service – as it turned out, the last one Pawel celebrated – that he finally feels at home in a church. I think that it is such a church and that it should remain such – among other things for the sake of those who don’t feel well in any other church. The question is, how are we going to make it happen without you, Pawel?

Amen

After a year we must admit, alas: we probably didn’t…

[1] St. Martin’s Lutheran Church in Cracow where we sometimes held our services. In October 2013 we celebrated there the first anniversary of regular Episcopal services in Cracow. The service was presided by Fr. Rudnicki, and the sermon was preached by our dear friend from the United Methodist Church, the Rev. Dr. Gregory S. Neal. Unfortunately, it turned out to be the last service presided by Pawel.

[2] The People’s Guard, and later the People’s Army, were Communist partisan forces. Today their veterans are ignored or even treated as traitors or Soviet agents.

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mieczysław_Moczar

[4] In 1968 took place an internal conflict among Polish communists. One camp comprised a nationalistic group, people who fought in the partisan forces during the war, led by Mieczyslaw Moczar, and the other a more cosmopolitan and liberal group, people who spent the war in the Soviet Union. Because many of them were Jewish and supported Israel, Moczar and his party used anti-Semitic slogans. As a result of this campaign, many Jews, especially the intelligentsia, left Poland. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1968_Polish_political_crisis

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthroposophy

[6] It is where we held our services.