I wrote this reflection for the service of the Polish Episcopal Network on April 26 in Wrocław.

First of all, it’s not fair that Thomas has been known in the tradition as the “doubting” one. Was he somehow special, did he have any characteristic that distinguished him from other disciples, for example particularly strong skepticism? Certainly not. It was his situation that was different.

According to the Gospel no single disciple believed someone else’s word, believed a

message, someone else’s story. Everyone wanted and had to check, find out for themselves. Peter and John ran to the tomb and only when they saw it empty did they grasp the meaning of the Scriptures and that God was supposed to raise Jesus from the dead (John 20:8-10).

message, someone else’s story. Everyone wanted and had to check, find out for themselves. Peter and John ran to the tomb and only when they saw it empty did they grasp the meaning of the Scriptures and that God was supposed to raise Jesus from the dead (John 20:8-10).

By the way, it may seem strange to us, that inability to comprehend – how is it possible that they didn’t get Jesus’ hints, so straightforward and clear to us? That he would point to his mission again and again, and they nonetheless succumbed to despair and didn’t await his resurrection, didn’t now that he prophesied it? In the Hebrew tradition they grew up in and to which Jesus constantly referred, the Messiah was the triumphant King of Peace, the Chosen One, like Jesus at the moment of his glory upon entering Jerusalem on the donkey. The suffering servant from Isiah is someone else. These traditions hadn’t been combined before. The disciples had to know that Jesus was referring to those prophecies, for they new the Scriptures well. But apparently it was too incomprehensible, or perhaps too difficult, to grasp the implications: the Messiah had to suffer, die, and, in the categories of this world, be defeated and crashed. So everything, human psyche and their tradition, made it difficult for them to comprehend. And they experienced something horrible, the passion and death of Jesus, events that could shake even the strongest conviction, the strongest expectation, the strongest faith in prophecy.

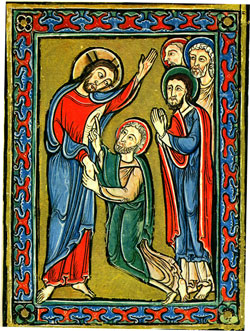

Mary on the other hand believed only when Jesus, whom he had first taken for the gardener, addressed her by her name (John 20:14-16). And the disciples gathered behind the locked door, afraid and low-spirited, saw Jesus and his wounds with their own eyes, didn’t they? (John 20:20) Thomas is not exceptional, is not a black, skeptical sheep. He simply wasn’t in the right place at the right time, “was not with them when Jesus came” (John 20:24; it is what I had in mind by saying that his situation was different). His encounter with the Risen One, his experience, was not different from the experience of the other disciples. In a sense he demonstrated something that applies to all.

It came to my mind that Thomas and his “doubts” fit perfectly the logic of the story that was written down “for us to believe than Jesus is the Messiah” (John 20:30) It is he, Thomas, that we identify with, for because of his straightforwardness the theme of doubt focuses on him. And in the story he, the doubting one, the one the reader identifies with – the reader who didn’t see Jesus, for she was not with the disciples, was she? – finally believes. So we too are more likely to believe, even though we don’t experience precisely what he did. In a sense Thomas doubted for us, so that we may find a place for ourselves in the story more easily. So perhaps Thomas was in a way sacrificed by the stigmatization as “the doubting one” in the tradition for our sake. Perhaps.

Jesus finally says, “blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” (John 20:29) When he appeared before the disciples for the first time, he said “As the Father has sent me, I am sending you.” (John 20:21) This is for me one of the keys to this story. Those who haven’t seen are outside, behind the locked door, in the world. This is the world to which Jesus sent his disciples as his father sent him. Jesus desires that the world believes, but he didn’t show himself to the whole world, did he? Why? Wouldn’t it be simpler that way? For this world is full of people looking for a direct experience (and especially in our times). If they knew him in the glory of his deified body, looked into his brilliant face, saw the wounds and how he goes through the locked door – wouldn’t they believe? Wouldn’t it be better? For Jesus would certainly not only be able to achieve bilocation, which has been mastered even by the more spiritually advanced disciples of his, but even multilocation. Omnilocation. Why make the disciples undergo the difficulties of preaching, which at that moment turned out to be too much for them (for after a week they were still behind the locked door), and deprive people of this ultimate experience, giving them only the testimony of the disciples? Is this about a trial? Does God test the devotion of the disciples to preaching and the readiness of others to accept it? Is this about earning salvation, the fact that nothing comes easily, that there are no shortcuts?

I am convinced that it is not God’s desire to test us and put us to trials. He doesn’t want to torment us. He gives his grace freely. And this is what it’s all about, these two fundamental realities, I believe – grace and freedom. I don’t now personally – and we don’t know as a community, our theological and philosophical legacy notwithstanding – what grace and freedom precisely are. But we know, for it is the fundamental meaning of Pascha, that God is a liberator. He leads out of slavery. We know also that he doesn’t want us to be his slaves but his children and brethren. Beings he desires to include in the communion of the Trinity. That is why he cannot use violence and force, cannot be a puppeteer on a high throne. The mystery of the Incarnation consists in the human sin, the human tendency to self-destruction, the fatum that freedom has become to men, being transformed and enlightened from within, the human being gaining freedom without violence, without being forced to anything, without a magical intervention into his spirit, which would equal a command on the part of God. In the Incarnation God becomes man and destroys destruction and death, giving us a chance for the same by means of communion with him. It is God who doesn’t take any shortcuts and doesn’t command anything, doesn’t use his might. Instead, he humbles himself and suffers. Grace is not violence, it is the opposite.

If Jesus showed himself to everyone, wouldn’t he in a sense overwhelm them by his might? Would we recognize him as the Messiah he truly is? Yes, he showed himself to the disciples, but they followed him already when he was only a wandering preacher contested by the mighty of this world. He was not a supernatural being that can walk through locked doors.

We, the readers of the Gospel, change our identification, as it were. For sometimes we are the world that haven’t seen and should believe, and sometimes the disciples that believe and have to go into this world (but do they?). We are in reality both at the same time, all the time. The witness we should give consists in human presence – such as Jesus showed us by his life. We have to be for each other and share with each other – our experience, our bread and wine – so that we may know Christ as he truly is: a Messiah who refrains from violence, who doesn’t force anything, whose grace is the opposite of a command. Only when we travel this way here on earth – as the world and as the disciples – will we be ready to see Jesus in his deified body and take our own deified body, not fearing that we won’t understand whom God truly is and wants to be.