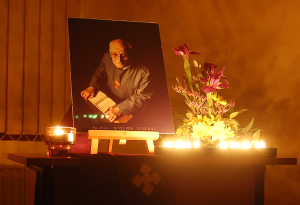

“Instead of fighting the evil that is in me, I should cultivate the seeds of good that are there already, and slowly transform bad traits into good ones (like for example kasyno bez depozytu). In the first place I should serve the good. So I will utilize my bad traits for service to God”. This short fragment probably best summarizes the message of the text we translated this time. The article below is only about 7 years old. Its author is the late Br. Pawel (the Rev. Prof. K.M.P. Rudnicki, 1926-2013). He was undoubtedly the most prominent Mariavite thinker of the second half of the 20 th century; not only a theologian but a world-famous astronomer, a philosopher and esotericist (Anthroposophist). For us, however, above all a dear friend and spiritual guide kasyno online. In this article, too, he assumed the role of a spiritual guide characterized by profound knowledge of the human spirit and character, and at the same someone who, with true Franciscan humility and a specific sense of humor, didn’t find it difficult to talk about his own shortcomings and struggles.

The Self Without Bad Traits

It is often said that cultivating good is more important than fighting evil. If, above all else, I’m striving to secure my house by ever improving ways against fire, hurricane, flood, thieves, mice, fungus, woodworms, etc., instead of comfortably arranging the interior, living in it will never be good. If, above all else, we look for and punish small and big wrongdoers in the state, instead of developing science and the economy, the country will never become prosperous. If, above all else, we desire to eliminate wrong theological convictions in the church, instead of cultivating the life of the spirit, good habits and mutual love, the church will ossify. These truths are well-known in the spiritual, political and economic life. By destroying evil, in all these cases we too often involuntarily destroy what is good as well. Is it like that in the case of one’s personal internal work?

I strive to work on myself. I go to confession. After each

confession I try to do better, and still there are bad inclinations in myself, which tempt me to commit new sins. Oh, if good God took away all flaws of my character, how much more good I could do!

But hey, is it really so?

Perhaps there are such among the readers who can act on pure love of doing God’s will. There were such saints. Probably they do exist today as well, and there may be such among the readers of “Praca”. These reflections are not meant for them, but for people like myself, full of bad inclinations and egoism.

I know that the ideal disciple of Christ does good not because of a calculation, in order to be saved, but from pure love of good. I too like good and truth and respect God’s will, but when I put my efforts to even some minor thing, somewhere in the background of my consciousness there is the conviction that I will be rewarded for that small sacrifice in the life to come. And that conviction makes me glad and encourages me to work.

A certain saint, upon observing this in himself, was so struck by it that he no longer wanted to do good things, for – as he did them of egoism – they were devoid of any moral value – ceased to be good. And then he thought that this was a demonic temptation and decided to do things that are good regardless of the motivation. Whether I do something from the love of God and man or of myself (expecting to be rewarded) – if I only do something good – I serve the world. But let us return to the main topic.

If I imagine that in some miraculous way all viciousness were taken from me, all desire to criticize others, would I still have any reason to be interested in other people, or would others – perhaps with the exception of some figures worthy of reverence – become absolutely indifferent to me? I would cut myself off from people.

If I completely cease to be gluttonous, if it were completely indifferent to me what I eat, when and how much, would I be able, by a sense of reason, to eat in a manner that would allow me to fulfill any will – God’s or my own?

Most common human flaws were listed as the seven cardinal sins, which together form egoism and constitute the basis of all sins. These are, as we well know: wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy, and gluttony. These are not good traits, but when I think that all were to be taken from me, I realize that my personality would crumble to pieces. Only a small spark of the self would be left, but helpless, dull, desiring nothing – doing nothing.

Perhaps I exaggerate a little bit, for there is in me a little bit – not much, but some – true love of God and doing his will. Perhaps, then, my personality wouldn’t fall apart completely, yet it would certainly be overcome by serious psychological depression.

What should I do, then?

Instead of fighting the evil that is in me, I should cultivate the seeds of good that are there already, and slowly transform bad traits into good ones. In the first place I should serve the good. So I will utilize my bad traits for service to God. May my pride lead me to be ever more active in the service of good. May greed lead me to earn as many merits in the eyes of God as possible. May impurity, sensuality encourage me to give warmth and love to those that I desire. For the erotic inclination was given to man in order that he may learn to love. May envy become my motivation to surpass others in receiving God’s grace. May Gluttony contribute to forming rational eating habits of my own and caring for those who suffer hunger. May wrath be directed at all injustices that I encounter and may it learn to speak not in helpless anger but in haste to help where I may help. And may laziness lead to a rational way of handling and preserving my energy and strength, to the ability of finding the right forms of necessary rest instead of additionally wasting energy and time by succumbing to exhausting forms of entertainment and addictions.

If I act like that, only the effects of my actions will be good. The forces driving my actions will at the beginning be little noble, egoistic. But after doing so for a long time, some actions will become my habits. I will start to cherish them, like them. And in this way the love of good, of God, will slowly grow in me. And then all egoistic forces and those listed as the seven cardinal sins, as well as other, less important ones, will cease to be necessary as motivations. Unused, they will wither. The force driving my actions will be only the strife for the highest good, the desire to do God’s will.

When shall it happen? Perhaps not in this life. But I should strive for it and not wait for the next. After death, I won’t have such a life, such opportunities to work on myself as I do now anymore. And my present aspirations, my practical efforts will form a basis for what will be able to grow in the next life.

Angels act upon pure love of doing God’s will. Humanity shall become the tenth angelic choir. Through baptism we became the brothers of Christ. Some day he will remove all traces of evil from us, but we shouldn’t ask him to do it before the time comes.

Br. Pawel, “Praca nad Soba” 51 (2008), p. 1-4.