A few days ago I posted this funny cartoon on Facebook. I was very much surprised by a commentary written under it:

I often see on your Facebook page memes depicting Episcopalians perpetually looking for something in a book (I even remembered that it’s “The Book of Common Prayer” because of them). Only I don’t know what it’s about; does it present Episcopalians as people having instructions and guidelines for every function and action in life? What is this about?

For a moment I was speechless. Is it possible that somebody really thinks of us as people “having instructions and guidelines for every possible function and action in life?” After a moment’s consideration I concluded however that it’s not something to be surprised by. The special relationship of Anglicans and their Prayer Book can cause misunderstandings, especially among people who had not come in touch with Anglican spirituality before. So I decided to write a few words about it.

A church without qualities?

In the years 1921-1942 the Austrian modernist writer, Robert Musil, wrote the novel “A Man Without Qualities.” Its main character, Ulrich, is a man without a clear identity, clearly defined individual features, or perhaps in a strange way indifferent to them. Sometimes Anglicanism is described in similar terms. To a degree it is correct. I talked about this in the sermon preached at the retreat of the Polish Episcopal Network in Kiekrz near Poznan in September 2012:

One of the reasons we have gathered here is to learn about the Anglican tradition. So there is nothing strange in the fact that as the hosts, yesterday and the day before yesterday, we have been confronted with questions about the “specificity” of this tradition, about its characteristic elements. What do Anglicans believe in? What is their position on this or that issue? How do they pray? This all comes down to one basic question: What is Anglicanism actually? Step by step it became clearer and clearer that the characteristic feature of Anglicanism is… that it has actually never wanted to have any characteristic features, that it simply wanted to be Christian – in a sense without predicates, without redundant defining features. And when some predicates were used, they actually pointed at the impossibility of putting on us any label known from the history of the church. So we talked for example about the Anglican churches being (both) Catholic and Reformed. Catholic, because they stress the continuity of the Christian tradition since its very beginning, and Reformed, because they are aware of the need to deal with it with criticism, which is exemplified not only by the 16th century Reformation, but also many subsequent reforms and changes. If we fulfilled our task well, in the course of these conversations one more thing should have become apparent – that, according to Anglicans, the question about what Christianity is can be often not answered otherwise but by another question, which then in its turn brings forth yet another question, etc., etc…

People seeking “hard identities,” expecting the church to give them answers to all possible questions, will be without a doubt disappointed at the Anglican way of being Christian. Against the background of other Reformed traditions, Anglicanism is distinguished by the lack of documents such as the Augsburg Confession, the Second Helvetic Confession, Luther’s Small and Large Catechisms or the Heidelberg Catechism. That is why it’s often difficult for us to define our church’s peculiar features. But the problem is not that there are none! Contrary to what may seem, the Anglican Churches are not “Churches without qualities.” The thing is that they are not to be found in any doctrinal document. Their medium and form of expression is the liturgy – the way we worship together “in the beauty of holiness.” Anglicanism can be seen as an incarnation of the ancient principle “lex orandi, lex credendi.” (Paraphrasing: “the way you pray is the way you believe.”) In this regard it has a lot in common with Orthodoxy. As often as one hears the words “Orthodoxy is liturgy” one hears the statement of the Archbishop of Canterbury Michael Ramsey (1904-1988) who said that Anglican theology “is done to the sound of church bells.” That is why our “symbolical book” is not a confession or a catechism but a prayer book.

So far so good, but in practice it turns out that the Anglican commitment to the BCP leads to misunderstandings.

Is it really a “prayer book?”

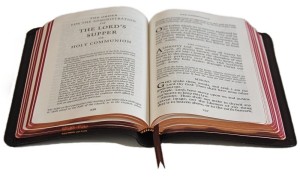

Perhaps we should start with the name. What do we associate the word “prayer book” with? I have a strong impression that most Polish people upon hearing the word see a book with more or less kitschy “holy pictures” sticking out of it, laying on the shelf beside grandmother’s wool hat. I’d like to emphasize that, the irony notwithstanding, it is not my intention to offend anyone. The point is only that the

book we call the BCP is – despite similarity of names – something else. Already at the first glance you can see that it combines features of a breviary and a missal, but contains also a range of elements exceeding those categories. Sometimes it seems to me that it would be more appropriate to speak about it as of “an Anglican’s vade mecum/handbook/manual,” containing the minimum of what you have to take departing on “the Anglican journey.” So the term “prayer book” does not cover all that it is, but the fact that this minimum has a form of a collection of liturgical prayers, and not for example a theological treatise, is very meaningful. For it shows that from our point of view it is fundamental that prayer shapes doctrine, even though we are aware of the mutuality between doctrine and liturgy (that is, that they influence each other).

book we call the BCP is – despite similarity of names – something else. Already at the first glance you can see that it combines features of a breviary and a missal, but contains also a range of elements exceeding those categories. Sometimes it seems to me that it would be more appropriate to speak about it as of “an Anglican’s vade mecum/handbook/manual,” containing the minimum of what you have to take departing on “the Anglican journey.” So the term “prayer book” does not cover all that it is, but the fact that this minimum has a form of a collection of liturgical prayers, and not for example a theological treatise, is very meaningful. For it shows that from our point of view it is fundamental that prayer shapes doctrine, even though we are aware of the mutuality between doctrine and liturgy (that is, that they influence each other).

Misunderstandings and problems

The fact that somebody I know recently interpreted this as an expression of depreciating theology’s role in the church surprised me no less than the commentary on Facebook which inspired me to write this text. Theology is very important to that person and this made him distance himself from the words we wrote in the information leaflet of the Polish Episcopal Network:

The specificity of Anglicanism is based on liturgy rather than on theological speculations. That is why the only really appropriate answer to the question what Anglicanism is about is: come to our service in order to “worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness” (Psalm 28). You’re welcome!

My surprise resulted in the first place from the fact that I too consider myself to be a man for whom theology is very important. Before I used to meet rather with the accusation of being “too much a theologian” than with the suspicion that I depreciate the meaning of theological reflection. The Anglican tradition, even if it didn’t give birth to that many theologians comparable to Luther, Bonhoeffer or Barth (but also in continental Protestantism they weren’t born daily!), doesn’t question the value of good theology to the church too. Not without a reason at the conference of the Polish Episcopal Network in January we devoted so much attention to the formation of our leaders, including theological formation. Although it’s not only about education, there is no doubt that even in our difficult Polish circumstances that put certain limits on us in this regard, the Polish Episcopal Network doesn’t want to be a community where will alone, without any preparation, is enough to become a leader. Despite all difficulties, we feel obliged to realize what Bishop Pierre Whalon of the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe wrote some time ago:

Another aspect of the Anglican method is an emphasis on education and scholarship. Of course, we share this with other Christians: a church that does not teach is no church at all. But our peculiar approach to tradition requires communal reasoning, and we think this must be as widely informed as possible.

It has always been important to Anglicans that this emphasis on education and scholarship shouldn’t regard theology alone. That’s why the Anglican method has often made the impression of being strongly rooted in general humanistic reflection, in literature, art, poetry or sciences. But it certainly doesn’t mean depreciation of theology as such. What then did we want to express by the statement that caused doubts and even rejection? In the first place the fact that there is no single Anglican theology. There are many and from the very beginning they were done in a possibly broad ecumenical context – in dialogue with representatives of other traditions. And precisely because of this variety no single one of them can be seen as a distinguishing feature of Anglicanism. But all their authors, proponents and opponents, were and are united by one thing – a common liturgical tradition.

Last year eight years passed since I began my ministry in the ecumenical base community Kritische Gemeente IJmond in the Netherlands. The history of the base movement is inseparably bound to changes in the liturgy. It can be said, of course simplifying the matter somewhat, that its first representatives were the most eager proponents of the post-Vaticanum II liturgical reform in the Roman Catholic Church. In any case the freedom of approach to traditional liturgical forms, including their thorough revision or even complete rejection and replacement by new ones, became one of the leading slogans of the base movement. The possibility to depart from traditional liturgical forms, even if in their place came nothing or an intuitive commitment to forms developed by the KGIJ itself in the course of the forty years of its existence, is for most members a litmus test of freedom as such. Already from the way I write about it you can certainly see that I have doubts regarding this approach. And indeed: the encounter with the base movement was the impulse that pushed me towards the Anglican tradition, which has a different approach to the liturgy. What does “different” mean, though?

People who see the Episcopal Church in the first place as liberal, giving its members lots of room for their own spiritual search, are surprised by a certain “liturgical rigidity” they encounter in the Polish Episcopal Network. It cannot be ruled out that it is due to a kind of “neophyte zeal.” If we chose Anglicanism, we try to do everything “properly” and perhaps not always fully use all possibilities of creative use of the liturgy. It is in any case something we should think about, in my opinion. But on the other hand I believe that one should first work out certain habits, and only then – consciously – perhaps depart from them. Be it as it may, Anglicanism understood as the Polish Episcopal Network understands and practices it undoubtedly won’t find favor not only in the eyes of the seekers of “clear answers and unquestionable truths.” Also people who treat the liturgical “play” in the first place as a set of limiting rules and boring, soulless forms won’t find it easy to find their place among us, unless they are ready to revise their approach.

This said, I would like to emphasize that we think it

important that the liturgy remains, according to the original meaning of the word, a work of the people, not protected by any taboo. Please read these words as an encouragement to speak to the officiants when you think that I or the others forget about this. This doesn’t change the fact, however, that Episcopalians certainly won’t become proponents of replacing traditional liturgical forms with improvised prayer, which results not from rigidity but all I wrote above the meaning of liturgy as the medium and keystone of the Anglican tradition. A Lutheran or a Presbyterian, even if they feel to a degree bound by the liturgies of their churches, have it easier to depart from them, because they can always say that what they do doesn’t violate the content of their symbolical books. Also a Roman Catholic can allow himself a significant outburst of “creative diarrhea” in the liturgy (which doesn’t mean they should) as long as they don’t violate the dogmas of their church. Anglicans, however, don’t have either symbolical books or THEIR OWN dogmas (only accepts the teaching of the ancient church). They only have their “handbook.” The key to understand the meaning of the BCP in the Anglican tradition is, I think, this very fact that it is much more than only a prayer book. Perhaps its worthwhile to ponder on this in the group of translators of the BCP into Polish. Shouldn’t we look for another word to express the content and importance of this book?

important that the liturgy remains, according to the original meaning of the word, a work of the people, not protected by any taboo. Please read these words as an encouragement to speak to the officiants when you think that I or the others forget about this. This doesn’t change the fact, however, that Episcopalians certainly won’t become proponents of replacing traditional liturgical forms with improvised prayer, which results not from rigidity but all I wrote above the meaning of liturgy as the medium and keystone of the Anglican tradition. A Lutheran or a Presbyterian, even if they feel to a degree bound by the liturgies of their churches, have it easier to depart from them, because they can always say that what they do doesn’t violate the content of their symbolical books. Also a Roman Catholic can allow himself a significant outburst of “creative diarrhea” in the liturgy (which doesn’t mean they should) as long as they don’t violate the dogmas of their church. Anglicans, however, don’t have either symbolical books or THEIR OWN dogmas (only accepts the teaching of the ancient church). They only have their “handbook.” The key to understand the meaning of the BCP in the Anglican tradition is, I think, this very fact that it is much more than only a prayer book. Perhaps its worthwhile to ponder on this in the group of translators of the BCP into Polish. Shouldn’t we look for another word to express the content and importance of this book?

As we have it about the title, we should also notice its another aspect. It is a book of COMMON prayer. What it tries to regulate pertains thus to the official worship of the COMMUNITY. Of course the BCP can also be used by individuals and it’a a good Anglican custom. Not without a reason Bishop Pierre Whalon said at our first conference that an Anglican is someone who prays from the BCP. On the other hand we should always remember that the Episcopal Church doesn’t tell anyone how their personal prayer life should look like. It only tries to unify forms of common worship. There is absolute freedom, for example, with regard to prayers with which each of us begins or ends our day and no church body will ever attempt to limit this freedom.

I would like to say a little more about another aspect of this freedom. Reading the BCP, and especially using it as it was meant to be used, we’ll easily notice that its so called “rubrics,” which fulfill a role similar to stage directions in a play, instructing how we should celebrate the liturgy, are very often suggestions rather than rules. So also an officiant who keeps to the rubrics still can make a lot liturgical choices of their own. In the Polish circumstances it is still not visible enough, because the translation work is going on and many liturgical and prayer “options” are not available in our language yet. We hope that once the Polish version of the BCP is completed, it will become clearer in how many ways we can shape the liturgical life of Polish Episcopalianism not exceeding the limits defined by the BCP – which are indeed very broad.

And will there come a moment to create a Polish Book of Common Prayer, which wouldn’t be a translation? At the January conference of the Polish Episcopal Network Bishop Pierre drew a broad perspective for the development of the Network. In the long term it should lead towards establishing an Episcopal Church in Poland in its own right. Such a church could of course take up the difficult task of composing its own book of prayer.

There is no single Book of Common Prayer

This last theme leads me to something I should have maybe

began with. The point is namely that talking about a single Book of Common Prayer is actually equally misleading as talking about a single Anglican church, which is alas still often the case. As there is no single church, but a communion of 38 local Anglican churches, there is likewise a whole family of Books of Common Prayer with many branches. They all have one ancestor in the Book of Common Prayer composed by

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

in 1549. Then the BCP underwent many changes, which led eventually to the 1662 version, until this day officially used in the Church of England. Over time came new local Books of Common Prayer, which started new branches of the BCP family. The 1979 American BCP, which we use in the Polish Episcopal Network in Polish translation, comes from the first BCP used in the Episcopal Church from 1790. It was based on the English edition of 1662 and the Scottish liturgy from 1764. Over time several revisions of the text were made, which led to the 1979 edition. It should be added that in Anglicanism a once authorized text can be thenceforth used always, also when the church introduces a new liturgy. So Anglicans don’t need special “indults” to use old rites as is the case in the Roman Catholic Church. So for example in the Hague parish of the Church of England on every first Sunday of the month the Holy Communion is celebrated also from the 1662 BCP – and we try to be there as often as possible. Interestingly, this liturgy has a “Polish trace,” for the Polish reformer

John a Lasco

(1499-1560) influenced the shape of the BCP. It is because of him that the Anglican liturgy contains the Ten Commandments, which, alternating with the Commandments of Love, are the Summary of the Law used to “examine the conscience,” which should lead to acknowledging one’s sinfulness before God and the need of grace and mercy.

began with. The point is namely that talking about a single Book of Common Prayer is actually equally misleading as talking about a single Anglican church, which is alas still often the case. As there is no single church, but a communion of 38 local Anglican churches, there is likewise a whole family of Books of Common Prayer with many branches. They all have one ancestor in the Book of Common Prayer composed by

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

in 1549. Then the BCP underwent many changes, which led eventually to the 1662 version, until this day officially used in the Church of England. Over time came new local Books of Common Prayer, which started new branches of the BCP family. The 1979 American BCP, which we use in the Polish Episcopal Network in Polish translation, comes from the first BCP used in the Episcopal Church from 1790. It was based on the English edition of 1662 and the Scottish liturgy from 1764. Over time several revisions of the text were made, which led to the 1979 edition. It should be added that in Anglicanism a once authorized text can be thenceforth used always, also when the church introduces a new liturgy. So Anglicans don’t need special “indults” to use old rites as is the case in the Roman Catholic Church. So for example in the Hague parish of the Church of England on every first Sunday of the month the Holy Communion is celebrated also from the 1662 BCP – and we try to be there as often as possible. Interestingly, this liturgy has a “Polish trace,” for the Polish reformer

John a Lasco

(1499-1560) influenced the shape of the BCP. It is because of him that the Anglican liturgy contains the Ten Commandments, which, alternating with the Commandments of Love, are the Summary of the Law used to “examine the conscience,” which should lead to acknowledging one’s sinfulness before God and the need of grace and mercy.

—

The few words I originally planned to write turned out to form one of longer posts on the blog. It is so when one thinks about writing something for a very long time. Thanking all who inspired me, I hope that my reflections will be on their part an inspiration to further reflection and discussion.